Rodney Brooks isn’t just any roboticist — he’s one of the most influential figures in modern robotics. As a co-founder of iRobot (maker of the Roomba vacuum), a long-time professor at MIT, and a visionary thinker who helped reshape how robots interact with the real world, Brooks has spent decades pushing robotics forward. Yet today he is sounding a sharp warning: much of the current excitement around humanoid robots and advanced AI-powered machines is built more on hype than on engineering reality.

Brooks’s critiques have sparked waves across the tech world. Investors, engineers, and researchers are asking whether the dream of human-like robots — the ones that walk, talk, manipulate tools, and work alongside people — is a realistic goal or a misguided pursuit.

Here’s a deeper look at his viewpoint, the broader context of robotics today, where the field may have drifted, and what the future truly holds.

Who Is Rodney Brooks — The Man Behind the Critique

Rodney Allen Brooks is an Australian-born computer scientist and roboticist whose work has shaped decades of autonomous machine design. Educated in mathematics and computer science, he served as a professor at MIT and led key research labs. Brooks co-founded iRobot, bringing the now-ubiquitous Roomba into millions of homes, and later Rethink Robotics and Robust.AI, ventures focused on practical, usable robots in industry.

His academic innovations — including subsumption architecture and behavior-based robotics — revolutionized how robots perceive and act in the world by prioritizing real-time responsiveness over complex internal world models, enabling simpler machines to work reliably in unpredictable environments. This philosophy helped shift robotics from research curiosities into genuine products.

Brooks’s Main Criticisms — Why He Thinks Robotics Has “Lost Its Way”

1. Humanoid Robots Aren’t Close to Human Competence

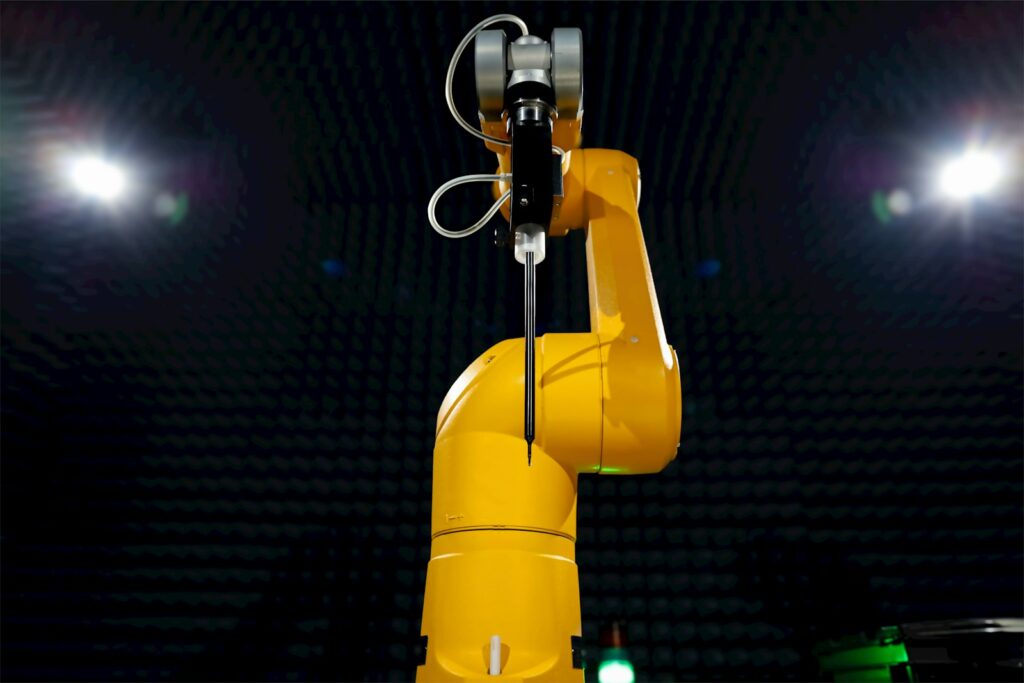

Brooks’s most vocal point is that today’s humanoid robots are nowhere close to matching human dexterity or reliability. Despite billions of dollars poured into humanoid projects (including Tesla’s Optimus and various research initiatives), Brooks argues that:

- Current approaches — especially those that rely on large data sets and training from video alone — cannot teach robots the nuanced physical skills humans take for granted.

- Human hands and human movement involve extraordinarily complex touch feedback and real-time adjustment that robots simply do not possess yet.

- Robots walking on two legs accumulate massive kinetic energy while balancing, making them unsafe to operate around people unless radically redesigned.

In his blog essays and talks, Brooks has emphasized that bipedal humanoid locomotion and manipulation remain engineering problems far beyond the current capabilities of learning-only methods. These are not minor software tweaks — they are fundamental mechanical and sensing challenges.

2. Hype Is Outpacing Engineering Reality

In Brooks’s view, much of the robotics industry has succumbed to magical thinking — the idea that advanced AI alone will suddenly unlock human-level robot capabilities. He sees several problems here:

- Overreliance on AI hype: High-visibility demos and attractive press often confuse feasibility with possibility. A flashy video does not prove reliability, safety, or scalability in the real world.

- Misplaced investment: Capital and research talent are disproportionately drawn to humanoid projects, potentially starving more practical forms of robotics that could deliver real societal value now.

- Underestimating embodied reality: Simulated environments and visual learning systems aren’t enough. A robot interacting with the physical world must engage with unpredictable physics, friction, balance, and tactile feedback — a domain where current AI has glaring limitations.

Brooks argues that a return to pragmatic, embodied engineering — focusing on robots that solve real tasks with robust reliability — will yield better outcomes both economically and socially.

3. Safety and Human Interaction Are Understudied

Another concern Brooks highlights is safety. Physical robots that move, manipulate objects, and share space with humans pose risks that digital AI systems do not. Unlike software errors, mechanical mishaps can cause bodily harm. Ensuring safe operation around people requires:

- Better sensing and prediction of human motion

- Redundant safety systems

- Designs that prevent high-energy impacts

- Clear standards and testing before deployment

Without rigorous engineering and safety frameworks, the dream of personal humanoid robots could lead to unpredictable and dangerous interactions.

Where Robotics Has Made Real Progress

While Brooks is skeptical of humanoid robots in the near term, he doesn’t dismiss robotics entirely. Significant progress has been made in:

Warehouse and Industrial Automation

Robots that move goods, inspect infrastructure, or assist in factories are already delivering value. These systems are engineered for specific contexts and environments where constraints are known.

Service Robots (Like Roomba)

Early successes like the Roomba showed that simple, well-engineered robots for specific tasks do sell and improve lives. They operate within well-defined boundaries and have predictable behaviors.

Human-Robot Collaboration

Collaborative robots (“cobots”) that assist humans on manufacturing lines or in logistics show that robots don’t need humanoid form to be useful.

These successes reflect Brooks’s philosophy: solve real problems reliably before chasing sci-fi dreams.

Why Humanoid Robots Are So Alluring — Despite the Challenges

There are powerful reasons the field hasn’t abandoned humanoids:

- Intuitive Interaction: Humans naturally understand human form — a humanoid robot looks like it can do human tasks.

- General-purpose versatility: A machine that can walk and use human tools in principle could adapt to many jobs.

- AI and robotics convergence: Advances in AI perception, reinforcement learning, and large-scale data have fueled belief that physical embodiment will soon follow.

Yet Brooks’s core message is that perception does not equal manipulation — seeing and understanding a task doesn’t automatically confer the ability to perform it physically at scale.

The Broader Debate in Robotics Today

Brooks’s critiques align with a larger discussion in tech circles: progress in software AI (e.g., large language models and perception systems) has far outpaced embodied intelligence — the ability for robots to act in the real world with reliability comparable to humans.

Other experts argue that:

- Some breakthroughs could emerge from hybrid approaches combining machine learning with classical control theory.

- Certain robotic tasks (especially industrial or constrained environments) are ripe for rapid improvement even if human-like generality remains distant.

- Safety, ethics, and regulation must co-evolve with technical advances.

The debate is far from settled, but Brooks’s voice — rooted in decades of practical robotics experience — demands that enthusiasm be balanced with engineering realism.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Are humanoid robots impossible?

No — but current designs are far from achieving human-level dexterity and safety. The engineering challenges are deeper and more complex than many public narratives suggest.

Q: Why does Brooks think robots are unsafe right now?

Walking bipedal robots must balance using stored energy that can cause harm if they fall or move unpredictably. Without robust safety systems and radically improved mechanisms, close human interaction remains risky.

Q: What robotic successes have already been achieved?

Task-specific robots — like vacuum cleaners, factory arms, warehouse movers, and simple service robots — are proven and widely used where boundaries and environments are well-defined.

Q: What is Brooks’s robotics philosophy?

He advocates for practical, embodied robots that address real world problems reliably, rather than chasing general-purpose humanoid machines based on hype.

Q: Could future tech overcome these challenges?

Possibly — but it will require breakthroughs in physical manipulation, sensing, materials, and safety engineering, not just better AI perception or algorithms.

Final Thoughts

Rodney Brooks’s critique isn’t a dismissal of robotics — it’s a call for grounded realism and practical engineering focus. The future of robots will be shaped not just by imagination and investment, but by the hard work of solving the physical, safety, and interaction challenges that govern real-world robotics.

Humanoid robots may one day become commonplace, but as Brooks reminds us, the path there is neither short nor straightforward. Meanwhile, much of the real value in robotics today lies in machines that solve specific problems reliably — and that’s a horizon already within reach.

Sources The New York Times