In a field long dominated by broad-spectrum antibiotics—“nuke the entire microbiome just to kill the bad guys”—researchers at MIT and McMaster University are exploring a more surgical approach. Using generative AI, they identified a molecule named enterololin that suppresses a specific group of bacteria linked to Crohn’s disease flare-ups, while sparing much of the rest of the gut microbiome. That’s a major shift: using AI not just to discover antibiotics, but to map how they act within complex microbial communities.

Below is a more comprehensive exploration: what they did, why it matters, what was left out, and where this could lead.

What the MIT / McMaster Study Did — The Essentials

Here’s a refined summary of the work:

- Motivation: In inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s disease, antibiotic therapies are double-edged—they may reduce inflammatory bacteria, but also kill beneficial microbes, potentially worsening gut health over time.

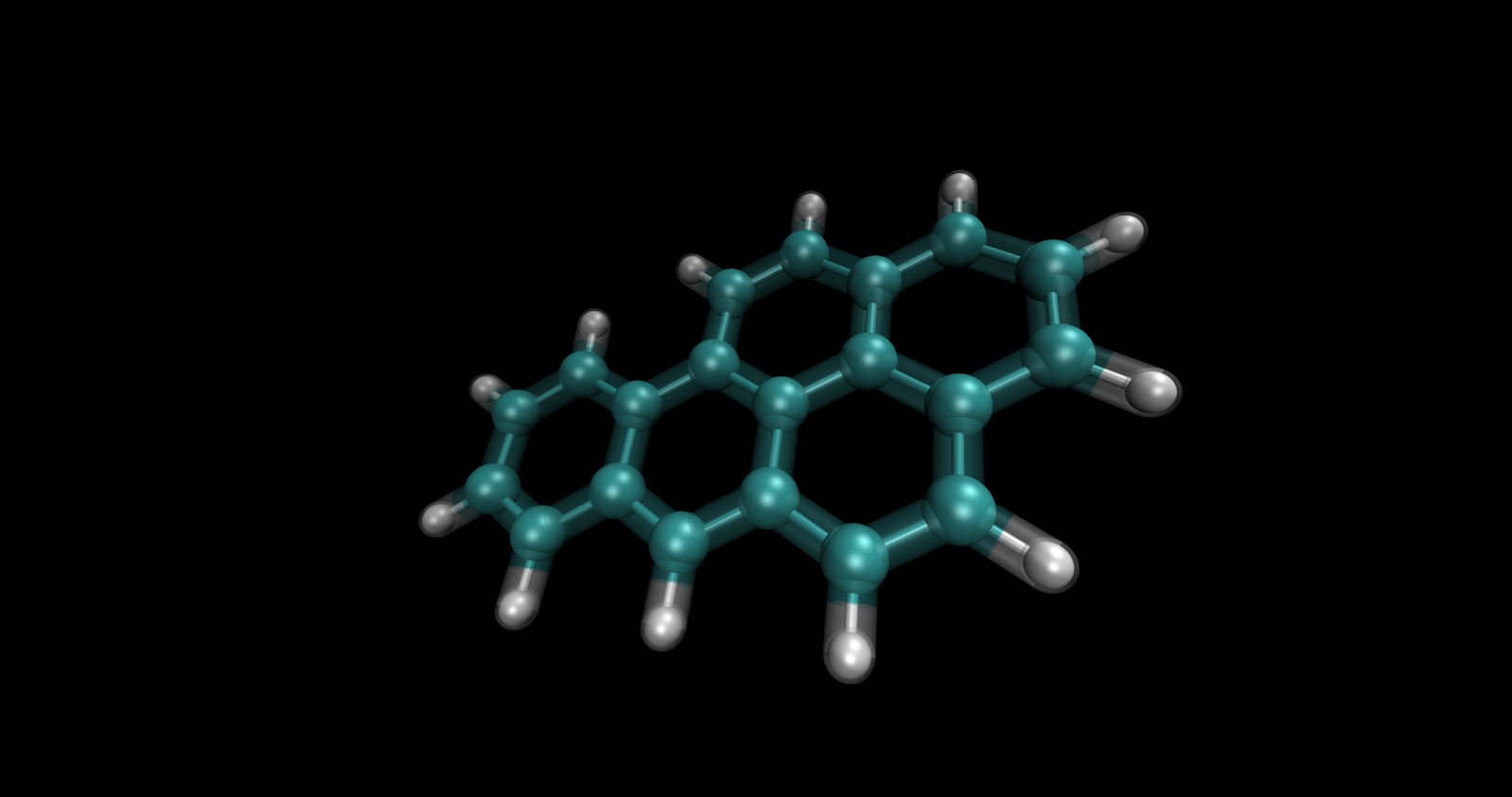

- Discovery of Enterololin: The team used a generative AI model to narrow candidates for molecules that might selectively inhibit certain gut bacteria populations rather than act broadly.

- Mechanism Mapping via AI: Beyond just discovering a molecule, AI was used to infer its likely mechanism of action—identifying how enterololin interacts with microbial pathways or cellular components. Traditionally, this mapping (from compound → bacterial target → downstream effect) takes years; the AI approach accelerated it to months.

- Selective Action: Enterololin reportedly suppresses a group of bacteria associated with Crohn’s flare-ups, while leaving much of the other microbiome relatively intact. This selective targeting is rare in antibiotic research.

- Collaborative cross-disciplinary work: The project involved both computational (MIT’s CSAIL / Jameel Clinic) and microbiology / biochemical teams (McMaster), combining AI modeling, microbial assays, and biochemical testing to validate predictions.

- Broader ambition: The team frames this as a proof of concept: not just finding new antimicrobials, but using AI to map specificity—i.e. who in a complex ecosystem is being affected and how.

What Was Underemphasized or Omitted — Deeper Considerations & Risks

To fully appreciate the significance (and limits) of this study, here are gaps or nuances the original article didn’t emphasize:

1. Validation Challenges & Off-Target Risks

- Predicting a mechanism in silico is only a hypothesis; experimental validation (mutant strains, knockout experiments, structural biology) is necessary to confirm the target. The article does not fully disclose how deeply that validation has proceeded.

- Off-target effects remain a risk. Even a “selective” antibiotic may inadvertently affect low-abundance microbes or trigger ecosystem cascades (microbiome shifts, resistance emergence).

2. Microbiome Complexity & Ecological Interactions

- The gut microbiome is not just a collection of isolated species; microbes interact (competition, symbiosis, cross-feeding). Suppressing one group can enable expansion of another, potentially harmful, group.

- Resistome transfer (horizontal gene transfer) and compensatory dynamics might erode benefits over time.

- Individual variability: the microbiome differs widely across individuals. A molecule that is selective in one person’s gut may act differently in another’s.

3. Generative AI Limitations & Model Bias

- The generative model is limited by training data. If most known antibiotic–target relationships come from lab strains, the model’s predictions for gut bacteria (which may be underrepresented) may be less reliable.

- The AI might favor molecular structures or modes of action that align with preexisting data biases, potentially missing more novel (but riskier) possibilities.

4. Synthesis, Delivery & Stability

- Even if enterololin is potent in vitro, delivering it effectively within the gut, reaching the microbial niche at adequate concentrations, resisting degradation, and avoiding toxicity to the host are all nontrivial challenges.

- Dosage, pharmacokinetics (how long the drug remains), metabolism by the host or other microbes, and stability under gut conditions (pH, enzymes) will test feasibility.

5. Regulatory & Safety Hurdles

- Safety to the human host must be rigorously tested (cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, off-target interactions). AI-based discovery accelerates generation, but safety studies remain slow and expensive.

- Because the approach is new, regulators will scrutinize mechanism-of-action claims, reproducibility, and long-term resistance risk more heavily.

6. Scale & Generalizability

- The study focuses on one target in one microbial context. Scaling this method to many gut microbes, or other microbial ecosystems (skin, oral, environmental), could hit diminishing returns.

- The generalization from one selective antibiotic to a pipeline of many will require optimization, robustness, and broad validation.

7. Economic & Access Barriers

- Advanced AI infrastructure, data curation, and experimental labs are resource-heavy. It may favor well-funded labs and biotech companies, potentially leaving resource-constrained regions behind.

- Patents, IP, cost of manufacturing, and commercial viability will decide whether enterololin or its successors become accessible treatments.

Why This Study Might Mark a New Phase in Antibiotic Science

If this approach proves robust, it could change how we think about antimicrobials:

- Precision microbiome editing: Rather than broad killing, future treatments might sculpt microbial communities—suppressing only harmful strains while preserving beneficial ones.

- Faster target mapping: AI-driven predictions of mechanism shorten discovery cycles dramatically, letting researchers iterate more rapidly.

- Expanding chemical space: Generative models can explore molecular structures beyond those in existing libraries, potentially unveiling novel scaffolds.

- Integration with microbiome diagnostics: Personalized profiling could guide which selective agents to use for each patient’s microbiome.

- Reduced collateral damage: By sparing much of the microbiome, risks like dysbiosis (microbiome imbalance) and opportunistic infections (e.g. Clostridioides difficile) may decline.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| 1. What exactly is enterololin? | It’s the AI-predicted antimicrobial molecule that suppresses certain gut bacteria associated with Crohn’s disease flares—with purported selectivity over other microbes. |

| 2. How sure are we about its mechanism? | The mechanism is predicted by AI; experimental validation is needed (e.g. binding assays, mutant bacterial strains). |

| 3. Will enterololin work in all patients? | Not guaranteed. Microbiome composition, host factors, and microbial ecology differ across individuals, which may affect efficacy. |

| 4. Can bacteria develop resistance to it? | Yes — resistance is always a possibility, especially with prolonged exposure. Monitoring and combination therapies may help mitigate that risk. |

| 5. How is this different from traditional antibiotics? | Traditional antibiotics are broad-spectrum. Enterololin is intended as more selective, killing only specific pathogenic groups, not the entire microbiome. |

| 6. How was AI used in this discovery? | Generative AI narrowed candidate molecules, then AI models predicted mechanisms and mapped likely bacterial interactions. |

| 7. What remains before it becomes a drug? | Further in vivo testing, safety and toxicity trials, delivery system development, regulatory approval, and manufacturing optimization. |

| 8. Can we replicate this for other diseases? | Potentially — the method could be adapted to other microbiome-related diseases (IBD, metabolic syndrome, infections), though each context has unique challenges. |

Conclusion

The MIT / McMaster team’s work on enterololin showcases a compelling evolution in antibiotic science: combining generative AI with microbiome-aware targeting to move beyond the broad kill-all approach of the past. Though many hurdles remain — from validation and delivery to resistance and regulation — this work offers a vision of precision antimicrobials that sculpt, rather than decimate, our microbial ecosystems.

The promise is profound: treatments that fight disease with surgical specificity, preserve beneficial microbes, and accelerate discovery cycles. But whether enterololin or its successors will turn into safe, effective medicines depends on rigorous experimental follow-through, patient diversity, and long-term stewardship of antimicrobial innovation.

Sources MIT News