The phenomenon: a growing concern

“Brain rot” is a term used to describe the mental fog, reduced attention span, shallow thinking or cognitive fatigue that can result from consuming large volumes of low‑quality online content. While originally used in reference to human digital media habits, recent research suggests that this ecosystem may now involve AI as both tool and consequence — that our AI systems, and we ourselves, may be degrading in parallel.

The interplay between social media, AI and cognitive health unfolds on multiple fronts: how content is produced, how it’s consumed, how AI models are trained on that content, and how human attention and cognition respond. The result: a worrying feedback loop.

How and why the mix of AI + social media is particularly potent

1. Algorithmic amplification of low‑quality content

Social media platforms favour content that gets clicks, views, engagement — which often correlates with short‑form, sensational, style‑over‑substance media. When such content dominates our feeds, it can reduce opportunities for deep focus, nuanced reasoning or thoughtful reflection.

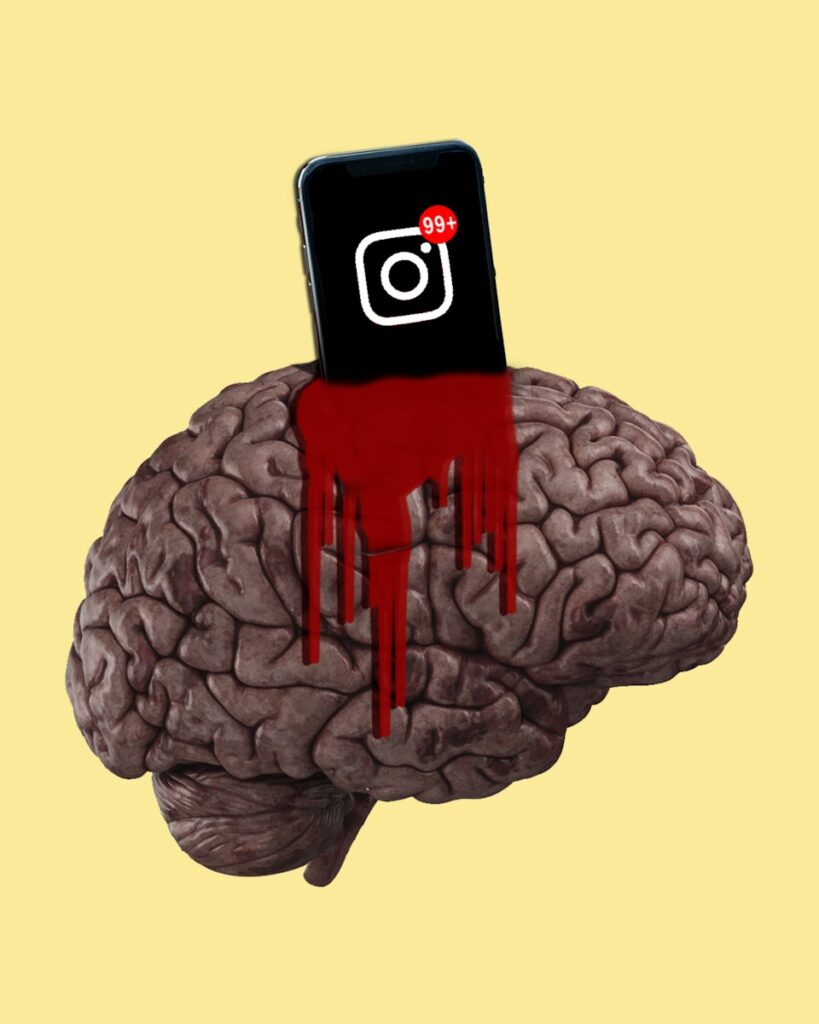

2. Consumption affects human cognition

Multiple studies show heavy social‐media usage (especially short‑form or high‑scroll interfaces) correlates with poorer attention, shorter sustained reading, more mental fatigue or distraction. “Brain rot” in this context can mean: difficulty concentrating, reduced memory recall, more superficial thinking.

3. AI’s role in production and training

- Platforms increasingly use AI to recommend or generate content geared for engagement rather than quality, exacerbating the “junk diet”.

- Separately, recent studies show that large language models (LLMs) trained on large volumes of short, viral social‐media style posts (rather than high‑quality curated text) show measurable declines in reasoning ability, memory for long‐context inputs, and ethical alignment.

- This means the very “training feed” for future AI may be degraded, creating models that perform worse or behave less reliably — mirroring the concept of human “brain rot” at a machine level.

4. Feedback loops and scale

- Lower‑quality content → shortened human attention → more engagement with same type of content → more low‐quality content produced.

- AI systems trained on such content output more shallow or engagement‑driven content → human users consume it → loop continues.

- Because AI and social media are so inter‐dependent (recommendation engines, generative tools, eyeballs), the risk is structural, not just incidental.

What recent evidence shows

- A major study found that LLMs trained on large volumes of “junk” social‑media posts (viral, clickbait, short‑form) experienced declines in performance on reasoning benchmarks, long‑context understanding and ethical alignment. The term “machine brain rot” was used.

- Researchers found a dose–response effect: the greater the proportion of low‑quality data in the training feed, the worse the model performed on reasoning tasks.

- Human studies correlate heavy use of highly engaging, shallow social media with reduced cognitive control, shorter attention spans, increased distractibility and less deep reading.

- Many AI‐generated or AI‐promoted social‑media posts are themselves low‑quality — raising concern that the data supply for future AI is self‑deteriorating.

Additional perspectives often missed or under‑emphasised

- Quality of attention matters: It’s not just how long you scroll, but what you consume. Rich, layered content (e.g., books, essays, long videos) engages different cognitive circuits than rapid small‐bite posts.

- Training data erosions affect future AI ecosystem: If AI models degrade (because training on junk), then future tools we rely on may be fundamentally less capable — with implications for productivity, reliability and decision‐making.

- Economic and business model drivers: Platforms and content producers are commercially incentivised to maximise engagement, not necessarily truth, nuance or cognitive richness. This structural commercial incentive is rarely foregrounded in the “brain rot” discussion.

- Differential vulnerability: Not all users, age groups or regions are equally impacted. Younger users, those with weaker prior habits of deep reading, or in high‐scroll environments may experience worse outcomes.

- Reversibility and recovery: For humans, reducing exposure and introducing deeper content can improve attention and memory over time. For AI models, the data shows partial recovery is possible but may not fully restore baseline reasoning once “brain rot” sets in.

- Ethical/algorithmic responsibility: Platforms, AI‐model builders and policymakers bear responsibility for how training data is curated, how content is recommended and how user attention is monetised. The “brain rot” phenomenon isn’t just individual failing—it’s systemic.

What you can do as a user

- Engage with long‑form, diverse content (essays, books, documentaries) to counterbalance short‑form social media diets.

- Designate tech‑free zones or times, especially during deep‑focus tasks or before sleep.

- Be mindful of scrolling for dullness (i.e., scrolling because you’re bored, tired or distracted) and pause to ask if the content is adding value.

- Use tools or settings to limit or filter attention‑sucking content (e.g., app timers, homepage resets, notifications off).

- For AI users: when using AI‑generated or recommended content, question whether the tool was trained on rich data—or just low‑quality scraps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What exactly does “brain rot” mean in this context?

A1: In this context, “brain rot” refers to the deterioration of reasoning, attention, or memory capacity due to prolonged exposure to shallow, high‑engagement digital content (especially social media). For AI, it means reduced performance in reasoning, context, ethical alignment when trained on low‑quality data.

Q2: Does this mean social media is always harmful?

A2: No. Social media can inform, connect, entertain and educate. The issue lies in how it’s used and what kind of content dominates. Exposure to rich, meaningful content and active, mindful use reduce risk.

Q3: How do we know AI models suffer this cognitive decline?

A3: Researchers conducted experiments training LLMs with varying mixes of high‑quality vs low‑quality data. They found that models trained with large proportions of viral/social‑media style posts performed worse on reasoning and long‐context tasks. The findings suggest a causal link.

Q4: Are we powerless to stop it?

A4: Not at all. Both platforms and users have agency. Users can manage their attention, diversify content diets and avoid endless unthinking scrolling. Platforms and AI developers can curate higher‑quality training data and avoid purely engagement‑driven optimisation.

Q5: What role do algorithms and AI play in this issue?

A5: Algorithms decide what content you see (via engagement metrics). AI‐models generate or recommend content. If those systems optimise for clicks/engagement, they favour shorter, sensational, less cognitively rich material. That steers user attention toward low‑quality content, which then becomes training fodder — creating a loop.

Q6: Is the “damage” reversible? Can attention/memory recover?

A6: For humans, yes—studies suggest sustained corrections (reading, reduced screen time, curated media) help restore focus and memory. For AI, initial experiments show partial recovery is possible but that full restoration may be harder once the model has internalised degraded data patterns.

Q7: What should policymakers or companies do?

A7: They should promote transparency in content‐recommendation systems, incentivise high‐quality content, hold AI‐model builders to data quality standards, support digital literacy, fund public‐interest media and ensure that attention‐economy incentives don’t override cognitive health.

Final Thought

The growth of AI and the ubiquity of social media mean that the challenge of “brain rot” is no longer just a personal issue. It now spans machines and humans, content and cognition, attention and architecture. Our digital environment is shaping how we think, how machines think, and how societies operate. Recognising the risk is the first step—then comes the work of rebuilding richer attention habits, better training diets, and systems designed not only for engagement—but for depth, responsibility and long‑term thinking.

Sources The New York Times