Artificial intelligence is no longer just assisting scientists with calculations or data cleanup. Today, advanced AI systems are being tested on something far more ambitious: the ability to perform meaningful scientific research tasks.

From forming hypotheses to analyzing experimental results, AI is increasingly being evaluated not as a tool, but as a potential collaborator in discovery. This shift has sparked intense interest — and debate — across academia, industry, and policy circles.

This article explores how researchers are evaluating AI’s scientific abilities, what current systems can and cannot do, what risks and limitations remain, and what this means for the future of science.

Why Evaluating AI in Science Matters

Scientific progress depends on rigor, creativity, and reproducibility. As AI systems become more capable, it’s no longer enough to ask whether they can generate fluent text or solve benchmark problems. The real question is:

Can AI meaningfully contribute to the scientific method itself?

Evaluating AI’s scientific capabilities matters because:

- Research is expensive, slow, and resource-intensive

- Many scientific fields face talent shortages

- Complex data sets exceed human analysis capacity

- Breakthroughs increasingly happen at the intersection of disciplines

If AI can accelerate even parts of the research process, the impact could be transformative.

What “Doing Science” Actually Means

To understand how AI is evaluated, it’s important to define scientific research tasks. These typically include:

- reviewing existing literature

- identifying gaps or open questions

- forming testable hypotheses

- designing experiments or simulations

- analyzing data

- interpreting results

- explaining findings clearly and accurately

Evaluating AI involves testing whether models can perform these steps reliably, independently, and with scientific validity.

How Researchers Evaluate AI’s Scientific Abilities

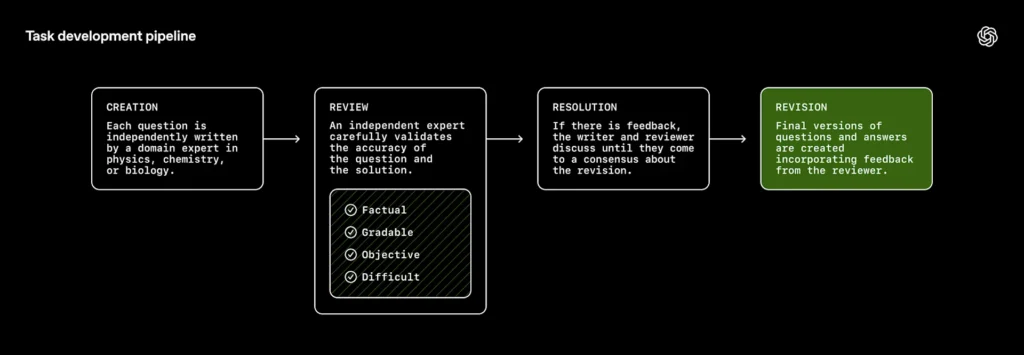

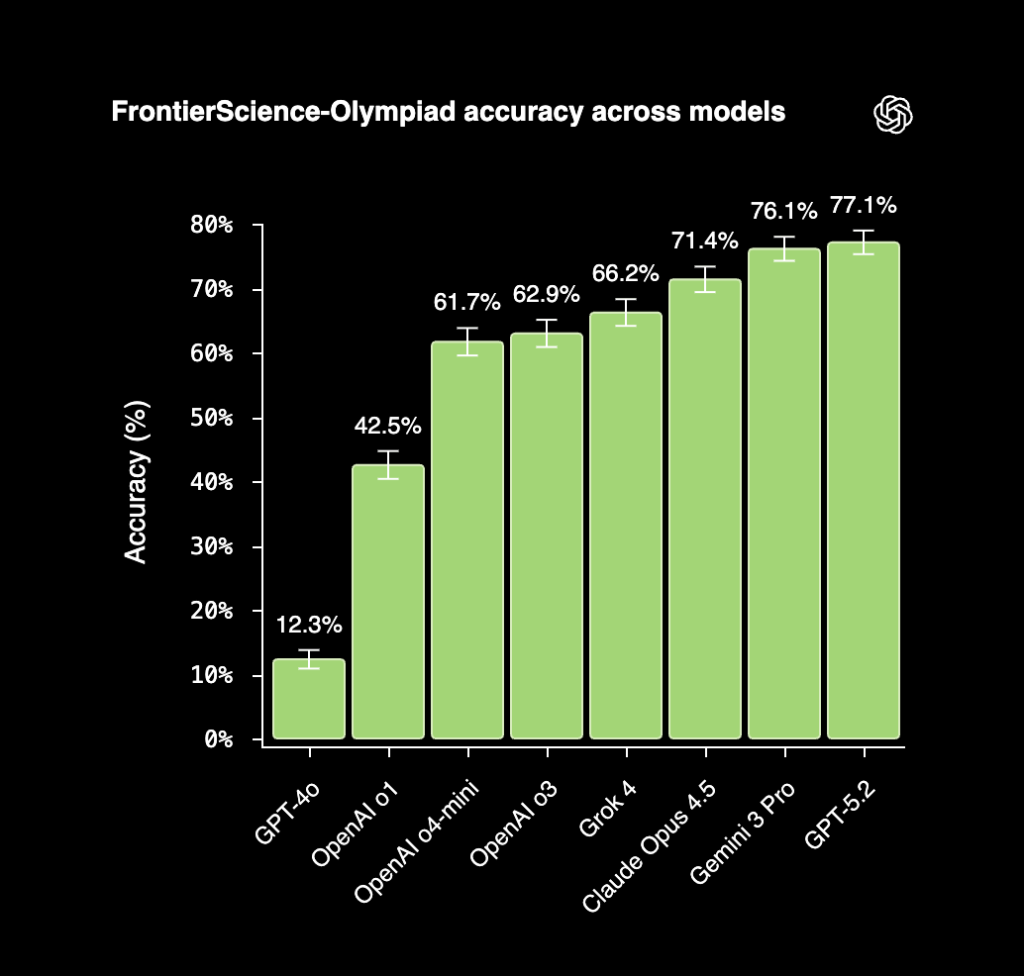

1. Task-Based Scientific Benchmarks

Instead of traditional exams or trivia-style questions, AI systems are tested on realistic research tasks, such as:

- summarizing and critiquing scientific papers

- proposing experimental approaches

- analyzing synthetic or real datasets

- identifying errors or inconsistencies in research logic

Performance is judged on accuracy, reasoning quality, and alignment with accepted scientific standards.

2. Multi-Step Reasoning Tests

Scientific work is rarely a single-step process. Evaluators test whether AI can:

- maintain consistency across long reasoning chains

- update conclusions when new evidence appears

- avoid contradicting earlier assumptions

These tests reveal whether models are reasoning or merely pattern-matching.

3. Domain-Specific Evaluation

AI performance varies dramatically by field. Systems are tested separately in areas such as:

- biology and medicine

- physics and chemistry

- materials science

- climate modeling

- social science

An AI that performs well in one domain may fail in another, highlighting the need for specialized evaluation.

4. Human Expert Review

Because scientific quality is nuanced, human researchers often review AI outputs to assess:

- plausibility

- originality

- methodological soundness

- ethical considerations

This hybrid evaluation remains essential.

What AI Is Already Good At in Science

1. Literature Navigation

AI excels at scanning massive bodies of research, identifying patterns, and summarizing findings across thousands of papers — something no human can do quickly.

2. Hypothesis Suggestion

By analyzing prior studies and data trends, AI can suggest plausible hypotheses that researchers might overlook, especially in interdisciplinary areas.

3. Data Analysis and Pattern Detection

Machine learning models can detect subtle correlations in large datasets, from genomics to astronomy, that would otherwise remain hidden.

4. Simulation and Modeling Support

AI can help optimize simulations, explore parameter spaces, and approximate complex physical or biological systems.

Where AI Still Falls Short

Despite impressive progress, AI is not a scientist — at least not yet.

1. Lack of True Understanding

AI does not possess conceptual understanding or intuition. It generates outputs based on patterns, not lived experience or insight.

2. Fragile Reasoning

AI systems can produce confident but incorrect conclusions, especially when faced with incomplete or ambiguous data.

3. Limited Experimental Judgment

Designing real-world experiments involves constraints, safety considerations, and practical trade-offs that AI struggles to fully grasp.

4. Reproducibility Risks

AI-generated research ideas may sound plausible but fail under real experimental conditions, making validation essential.

Why Evaluation Is Harder Than It Sounds

Evaluating AI in science is uniquely difficult because:

- many scientific questions have no single correct answer

- novelty is valued but hard to measure

- errors can be subtle yet critical

- progress often depends on context and judgment

This means simple scores or benchmarks are insufficient. Robust evaluation requires continuous testing, expert oversight, and real-world validation.

Ethical and Safety Considerations

As AI becomes more capable in scientific domains, new risks emerge:

- fabrication of convincing but false research

- accidental generation of unsafe biological or chemical insights

- erosion of trust in scientific literature

- overreliance on automated systems

Responsible evaluation must therefore include safety, misuse prevention, and governance, not just performance metrics.

What This Means for the Future of Science

AI is unlikely to replace scientists — but it will change how science is done.

In the near future, AI may act as:

- a research assistant

- a hypothesis generator

- a data analysis partner

- a cross-disciplinary bridge

The scientists who thrive will be those who know how to work with AI critically, not blindly.

The Bigger Shift: From Tools to Collaborators

Historically, technology has amplified human capability — from microscopes to supercomputers. AI represents the next step: tools that can participate in reasoning itself.

But participation doesn’t equal authority.

Evaluating AI’s role in science is ultimately about deciding where automation helps and where human judgment must remain central.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Can AI independently conduct scientific research?

Not fully. AI can assist with many tasks, but it lacks true understanding, creativity, and accountability.

Q2. What scientific fields benefit most from AI today?

Biology, medicine, materials science, climate modeling, and data-heavy disciplines.

Q3. How is AI performance in science measured?

Through task-based benchmarks, multi-step reasoning tests, domain-specific evaluations, and human expert review.

Q4. Is AI more reliable than human researchers?

No. AI can process more data, but humans remain essential for judgment, ethics, and interpretation.

Q5. Can AI generate new scientific discoveries?

AI can help identify promising directions, but discoveries still require human validation and insight.

Q6. What are the biggest risks of AI in science?

False confidence, fabricated research, misuse, and overreliance on automated outputs.

Q7. Will AI reduce the need for scientists?

More likely, it will change the role of scientists rather than eliminate it.

Q8. How can researchers use AI responsibly?

By treating AI as an assistant, verifying outputs, and maintaining human oversight.

Q9. Are scientific journals prepared for AI-generated research?

Policies are evolving, but standards and disclosure requirements are still catching up.

Q10. What’s the key takeaway?

AI can accelerate science — but only if we rigorously evaluate its limits as well as its strengths.

Sources OpenAI