For years, advanced semiconductor technology has been one of the most powerful pressure points in global geopolitics. As the United States and its allies tightened export controls on cutting-edge chipmaking tools, many assumed China’s artificial intelligence ambitions would slow dramatically.

That hasn’t happened.

Instead, China is quietly boosting its AI chip output by doing something less flashy but highly strategic: upgrading and repurposing older semiconductor machines already inside the country. By squeezing more performance out of legacy equipment from Dutch chipmaking giant ASML, Chinese manufacturers are proving that innovation doesn’t always require the newest tools — just persistence, engineering skill, and scale.

Why AI Chips Matter So Much to China

AI chips are not just another technology product. They sit at the core of:

- data centers and cloud computing

- facial recognition and surveillance systems

- industrial automation

- autonomous vehicles and robotics

- military and national security applications

For China, reliance on foreign chip suppliers represents a long-term vulnerability. Export restrictions on advanced semiconductor tools have made domestic production not just an economic priority, but a strategic one.

The Constraint: Limited Access to Cutting-Edge Tools

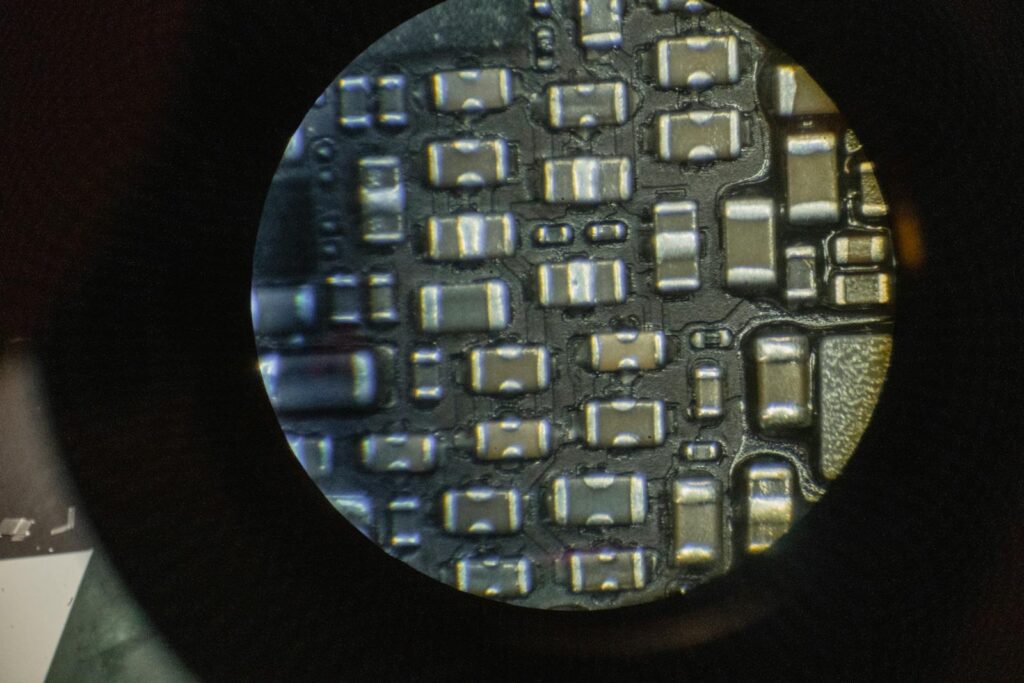

Modern AI chips are typically manufactured using extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, a technology controlled almost entirely by ASML. Under current export controls, China cannot access these machines.

However, China still possesses a large number of older ASML deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography tools, which remain highly capable — even if they aren’t state of the art.

Rather than viewing these machines as obsolete, Chinese chipmakers are treating them as assets to be optimized.

How China Is Getting More Out of Older ASML Machines

Chinese semiconductor firms are using several techniques to expand AI chip production:

- upgrading software and control systems

- tightening manufacturing tolerances

- running machines at higher utilization rates

- using advanced multi-patterning methods

- improving defect detection and yield management

These methods allow older machines to produce chips suitable for many AI workloads, even if they are less efficient than the latest generation chips made elsewhere.

The Trade-Offs China Is Willing to Accept

This approach isn’t perfect, and Chinese manufacturers are fully aware of the compromises:

- chips consume more power

- manufacturing costs are higher

- production is slower and more complex

- yields are harder to maintain

But for many AI applications, the chips don’t need to be the absolute best. “Good enough” performance at large scale is often sufficient, especially for domestic data centers, industrial AI, and government systems.

Why This Strategy Is Working

China’s advantage lies in scale and engineering depth.

Over the past decade, the country has invested heavily in:

- semiconductor talent and training

- domestic materials and components

- manufacturing process optimization

- long-term industrial planning

That ecosystem allows Chinese fabs to extract far more value from older equipment than many outside observers expected.

What This Means for Global AI Competition

China’s progress complicates a simple narrative that export controls alone can halt AI development.

Instead, the world is moving toward:

- parallel AI ecosystems

- different performance tiers

- fragmented supply chains

China may not dominate the most advanced chips, but it can still support widespread AI deployment at home — and that matters economically and strategically.

Implications for the Semiconductor Industry

This development sends several signals to the global chip industry:

- legacy equipment remains strategically valuable

- manufacturing expertise can partially offset hardware limits

- export controls slow progress but rarely stop it entirely

It also raises questions about how effective current restrictions will be over the long term without deeper coordination and enforcement.

What Comes Next

China is unlikely to stop here. The next phase will likely include:

- continued refinement of manufacturing techniques

- heavier investment in domestic lithography alternatives

- incremental improvements in chip performance and efficiency

Meanwhile, governments elsewhere face a difficult balancing act between protecting national security and acknowledging the adaptability of global technology ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is China increasing AI chip production without advanced tools?

By upgrading older lithography machines, improving manufacturing processes, and using complex patterning techniques.

Are these chips as advanced as the latest Western ones?

No. They are generally less efficient, but still powerful enough for many AI uses.

Why are ASML machines so important?

Lithography tools are essential for chipmaking, and ASML dominates this critical technology.

Do export controls still have an impact?

Yes. They increase costs and slow progress, but they don’t completely stop production.

Is China becoming self-sufficient in AI chips?

Not fully, but it is steadily reducing its dependence on foreign suppliers.

Does this affect global AI leadership?

Yes. It supports a more fragmented global AI landscape rather than a single dominant model.

What’s the biggest limitation of China’s approach?

Higher power use and more complex manufacturing processes.

Will China develop its own advanced lithography tools?

That remains a long-term goal, but it is extremely challenging.

Why did many analysts underestimate this strategy?

They underestimated how much performance could be extracted from older equipment.

What’s the key takeaway?

Even under heavy restrictions, technology ecosystems adapt — often in unexpected ways.

Bottom Line

China’s effort to boost AI chip output by upgrading older ASML machines shows that technological constraints are rarely absolute. Export controls have reshaped the semiconductor landscape, but they have also pushed innovation in new directions.

The result is a world where AI progress continues — just along different paths, at different speeds.

Sources Financial Times